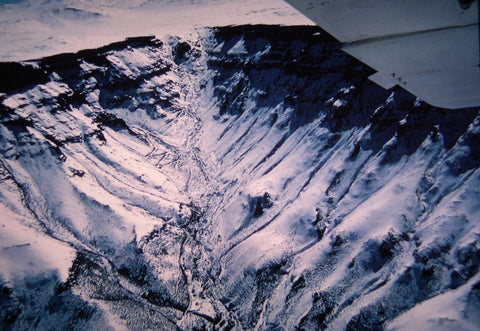

Sani Pass on descent from Kotisphola down to the Sehonghong river

By Beverley Eikli

(writing as B. G Nettelton for my Africa-set romantic suspense novels).

My earliest memories are of mountains and small planes.

And of regular hospital visits which meant difficult journeys from our home in Lesotho’s mountainous Mokhotlong district to Grey's Hospital in Pietermaritzburg, Kwa Zulu-Natal, across the border in South Africa.

I was born with a condition known today as hip dysplasia. While detection and correction are simple in the modern era, my "congenital dislocation of the hip," as it was called back then, went unnoticed until I was over 15 months old. That delay in diagnosis had huge ramifications for me and my family.

Early Days in Lesotho: Mountains and Medical Challenges

At that time, I was the only child of my parents, living in a remote and mountainous region of Lesotho and my inability to walk did not raise concerns until a family friend visiting my mother suggested that something might be wrong.

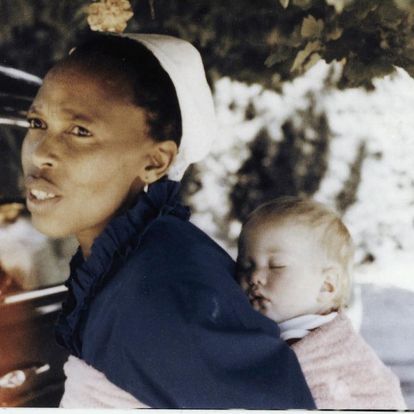

Mum with me as a baby

My granny and grampa Turner at our house in Mokhotlong

A young herd boy in the mountains near our home.

Lesotho's Independence and My Father's Role

During the months leading up to my birth in 1965, my father had been occupied with organizing Lesotho's Independence Celebrations. These were strategically scheduled for the following year to coincide with international heads of state coming to Africa for Botswana's Independence celebrations, which would be held a week earlier. They would therefore attend Botswana's Independence Celebrations on September 30, followed by Lesotho's on October 4.

While my father managed a tight budget to execute this vibrant and ambitious event to showcase national pride and the emergence of a new nation, my mother, like any expectant mother, was preparing for the arrival of a new baby.

Traversing the Treacherous Sani Pass

However, travelling by road from home in Mokhotlong to medical check-ups across the border in South Africa was not a viable option for a pregnant woman.

The difficult 40 miles journey from Mokhotlong to the top of the Sani Pass took three hours in a 4x4 land rover in the mid 1960s. And then there was the treacherous descent down the Sani Pass to navigate.

So mum generally flew by light aircraft from the bottom of our garden.

Locals on the Sani Pass

The Journey to Treatment: From Lesotho to South Africa

In those days, there were few roads in Lesotho's mountainous region. Much of my father's work required him to embark on treks that spanned several days, riding a sturdy Basuto pony along narrow and rocky bridle paths with steep ravines on one side. In winter, he would traverse snow-covered plains and passes.

The Sani Pass, which was constructed in the early 1950s, was, arguably, one of the world's most treacherous mountain passes during the 1950s and 60s when my parents frequently navigated its steep gravel gradients, some as high as 1:4.

The pass traverses the Great Escarpment of southern Africa at its highest point along the Drakensberg Mountains. Starting from 1,544 meters (5,066 ft), it ascends 1,332 meters (4,370 ft) over a distance of 9km, connecting the South African border control near Himeville to Lesotho Border Control at the pass's summit.

Me on the Sani Pass in 2010

Twists and Bends on Sani Pass

During my last visit to my childhood home in 2010, significant upgrades had been made to the Sani Pass. Nevertheless, the remnants of vehicles that had failed to negotiate its steep slopes and slippery surfaces served as a reminder to exercise caution, especially during winter when driving conditions become even more hazardous due to snow and ice.

The Sani Pass taken from above during one of dad's plane trips in the 60s.

So, I grew up on top of the world in what was known as "The Colonial Empire's Remotest Outpost" surrounded by majestic mountains.

In my upcoming book, Diamond Mountain, my protagonist Philippa, daughter of Mokhotlong's District Commissioner, finds herself torn between her love for the rugged Maluti Mountain range that surrounds her home and the grandeur of Table Mountain in cosmopolitan Cape Town, where she is studying.

These two mountains symbolize the romantic dilemma she faces, choosing between the adventurous bush pilot she loves and the affluent society lawyer who offers her the life she believes she’s always wanted.

Cover of Diamond Mountain by B G Nettelton, a romantic suspense novel set in Lesotho, Africa

You can read more HERE.

But I digress. Let's return to my story.

Once I was diagnosed with a lack of hip cup, which made walking either impossible or very painful, the doctors at Grey's Hospital suggested that my parents place me in a Crippled Children's Home in South Africa due to the difficulty of travelling for hospital visits.

Me in a plaster cast with mum's Pekingese, Lilibet

However, I had everything I really needed in Mokhotlong – loving parents and three household staff, including my beloved and wonderful nanny, Francina, who stayed with our family for many years until we emigrated to Australia. Her children, Mpho, Muketsi, and Ann Bubba, were my playmates in our beautiful garden overlooking a lovely dam with mountains as our backdrop.

Mum and me in our back garden in Mokhotlong

My nanny Francina with my sister, T.

I tried unsuccessfully to find Francina when I returned to Lesotho in 2010.

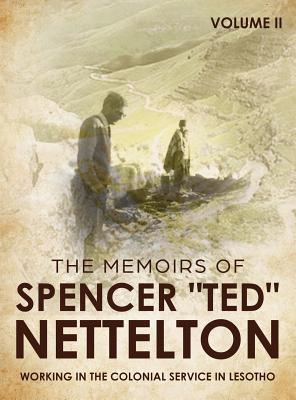

Both Francina and Mpho appear in my story, Diamond Mountain, albeit in fictionalized forms. Mpho plays a heroic role during a mob uprising triggered by a dispute over illegal diamond buying, which my father investigated as part of his work. Many of the events in Diamond Mountain are inspired by dad’s memoirs, "Working in the Colonial Service in Lesotho in the 1960s” by Spencer “Ted” Nettelton.

So, while placing me in a Home in South Africa was dismissed, so was relocating there due to South Africa's abhorrent Apartheid policy. Lesotho, my African mountain kingdom home, was geographically enclosed by South Africa, but Apartheid was the official racist policy of South Africa’s Nationalist government between 1948 and 1994.

Lesotho was first a British Protectorate before it became an independent African country on October 4, 1966, and while my parents would travel into South Africa for medical treatment, they’d never consider living there.

My father, who had been born and brought up in Botswana--another British Protectorate before Independence in 1966--had been sent to Lesotho (then Basutoland) in 1952 as a young District Officer working in the British Colonial Service.

So we remained in Lesotho which meant regular, arduous hospital visits across the border to have my waist-to-toe frog-leg plaster removed with terrifyingly large clippers, before it was replaced by fresh waist-to-toe plaster.

We would either fly out in a Cessna 172 from the Mokhotlong airfield, which was conveniently located at the bottom of our garden through a small metal gate, or travel down the Sani Pass in dad’s short wheelbase Land Rover.

Mum on trek in Lesotho

Despite the constraints of my plaster, I was an active child. I would quickly wear through the carpet squares my parents placed over the knees of my plaster as I dragged myself up and down stairs. To this day, I possess considerable upper body strength.

Later, when we moved to Australia, I was encased in a more linear type of plaster which made it much easier to get around. With wheels that dad attached to a surfboard, I was able to reach great speeds and, for the first time, outpace my younger sisters and peers.

Of course, none of the various plaster contraptions worked. The only solution to enable proper mobility was a successful operation to form a hip socket. And this had not yet been pioneered.

A Royal Appointment: The MBE and a Trip to London

When I was two years old, my father received an MBE (Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire) for his efforts in organizing the Independence Celebrations. It was therefore decided that our family trip to the UK for dad's investiture at Buckingham Palace would include a visit to the world's leading children's orthopaedic surgeon.

Lesotho on Independence Day, October 4

I remember mum saying that this surgeon was very condescending and refused her request to reschedule her appointment with him until she informed him of the clash with my father's investiture.

Dad’s Investiture was, by all accounts, exciting and rewarding, but my visit to the orthopaedic surgeon in the UK was disappointing after he initially agreed to perform an operation, but then unexpectedly reneged.

Granny, dad and mum at Buckingham Palace, in London, for his Investiture

So, we returned to Lesotho, with me wearing yet another peculiar, ultimately useless, leather waist-to-toe contraption adorned with numerous metal buckles.

A plane that came to grief and remained for a long time in the airfield near home.

Returning Home: New Challenges and Changes

Nothing changed significantly for me, but there were exciting changes afoot for the country, and for my family.

Lesotho gained its Independence and dad became Secretary to the country’s first democratically elected Prime Minister, Leabua Jonathan. He travelled to the US with the PM for Leabua’s Maiden Speech to the United Nations staying at Blair House where dad and Leabua were guests of then US President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Dad’s new job also meant a relocation to the capital, Maseru, where we lived in a beautiful stone house with different mountain views. I no longer wore plaster casts which had failed to produce the desired result; however, walking was painful as my hip was always slipping out of joint.

From Lesotho to Australia: A New Beginning

Finally, my parents felt the time had come to leave Lesotho, deciding upon a new life in Australia.

So, with dad’s “Golden Handshake” payout, we spent our first six months living on Lord Howe Island, a tropical paradise just off the coast of New South Wales. We flew there in in a Shorts Sunderland Flying Boat – another exciting flying experience as the islanders rowed out to welcome us and placed floral lays about our necks.

Arriving on Lord Howe Island on a Sunderland Short. When we returned 18 months later, I cried with disappointment that the days of flying boats had ended now that Lord Howe had a 'boring' runway.

Arriving on Lord Howe Island on a Sunderland Short. When we returned 18 months later, I cried with disappointment that the days of flying boats had ended now that Lord Howe had a 'boring' runway.

By the time I was seven, our family had settled in Adelaide, South Australia. I could walk, but not without pain and difficulty, so, my parents took me to the Royal Children's Hospital to visit a visionary children's orthopaedic surgeon named Dr. Dennis Patterson.

The Miracle Operation: Meeting Sir Dennis Patterson

He asked for permission to perform his ground-breaking operation, confident of a successful outcome based on his recent successful trials of the procedure on dogs' hips and my parents agreed.

As well as being a huge success, the operation was a “world-first” and my surgeon became Sir Dennis Patterson.

And at last, I could walk without pain.

I recall proposing marriage to Sir Dennis at his consulting rooms at the RCH. I also remember his gracious rejection, as he explained that he already had a wife and four children.

So there was the happy ending.

Sir Dennis was knighted, and I was the child who grew up with a disability, accepting I would never walk properly or without pain, only to suddenly receive the gift of mobility.

Like “the Little Mermaid” in Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tale which mum read to me when I was little, I would have willingly traded my voice for legs.

Unlike her, I got it all.

The little mermaid’s dreams of walking were made from the ocean floor, while mine were forged amidst the majestic mountain peaks that surrounded me.

And, like the protagonist in my story Diamond Mountain, I was inspired by those mountains, many years later, to make the right choice of husband: a rugged bush pilot.

Full Circle: From Mountain Dreams to Aviation Romance

Yes, Dear Reader, I chose the handsome Norwegian bush pilot whom I met in Botswana's Okavango Delta who has yet to visit my beautiful Maluti Mountains, even though he has flown in the course of his work as a pilot on all seven continents.

We now live happily in Victoria, Australia, with our younger daughter, but Africa still calls to me.

Perhaps our next thrilling adventure will involve soaring through the skies to the lofty peaks of Mokhotlong, my old mountain home.

This is the first of my memoir pieces about growing up in Africa and Australia, and of my flying adventures with my husband.

I will intersperse these blog posts with updates on my historical novels set in Regency, Victorian and Georgian England.